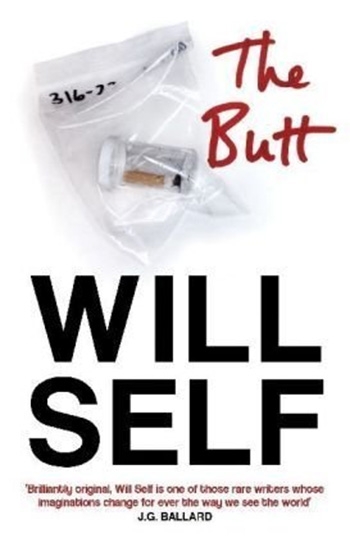

Will Self was once the enfant terrible of British letters, a former drug addict turned writer and satirist whose infamy peaked in 1997, when he was caught doing heroin on the private plane of former UK Prime Minister John Major, whose campaign he was supposed to be covering. “I’m a hack who gets hired because I do drugs,” was his depressing summary of his career at that point. By 1998, however, he began turning his life around, first by jettisoning the drugs and then by accepting steady work – as a columnist for the Times, the Independent on Sunday and the Evening Standard; as a guest panelist on various British talkshows; and finally as “Professor of Modern Thought” at Brunel University London. The Butt, Self’s eighth novel, was published in 2008; it takes us on a journey into the heart of a fictional country, from the perspective of a tourist (presumably American) who finds himself enmeshed in the cultural and legal traditions of the indigenous peoples after he accidentally causes injury to a man by flicking his cigarette butt off his hotel balcony.

I have no doubt made the novel’s premise seem more respectable and less absurd than it actually is. Our protagonist, Thomas Jefferson Brodzinski, is on vacation with his wife and children, and on one of the final days, with a return home in sight, he carelessly disposes of what he tells us will be his last cigarette: “Vainly, he cast about once more for the ashtray that wasn’t there; and then, in a moment of utter unthinking, he flipped the butt into the sodden air.” It lands on another American, Reginald Lincoln, someone Tom had seen earlier and mistaken for a sex tourist, since he is married to an indigenous woman decades his junior, and though the projectile cigarette causes Lincoln no physical damage – he even forgives Tom his carelessness – he has a cardiac episode later in the evening, and because of the obscure legal system of this unnamed country, which refuses to distinguish between intentional and unintentional harm, Tom is held criminally liable, forced to surrender his passport and await a trial. In these initial phases, Self seems to summon the spirit of Kafka’s Joseph K., the protagonist of The Trial, an innocent man railroaded by a byzantine bureaucracy, but the foreign setting – together with the protagonist’s being named after one of America’s founding fathers – also suggests an allegorical reading. An American citizen, in a foreign country, unthinkingly causes grievous bodily injury – are we now also in a post-colonial novel, Chinua Achebe by way of Kafka? A ballistics expert (!) is brought in by the local district attorney to assess the flight path of the cigarette butt, and he determines that its parabolic path through the air took it outside the private confines of the apartment complex and into public air space, where smoking is expressly prohibited. “No Ifs, No Butts, Stub It Out!” reads one sign.

From this point on, Tom is at the mercy of the local legal system, including his own attorney, Jethro Swai-Phillips, whose allegiances are, from the beginning, suspect: is he acting in Tom’s best interests, or merely seeking to extort the maximum amount of money from his client? Before we are allowed to find out, the trial happens – an anticlimactic affair, resolved rapidly, resulting in a verdict: Tom is guilty and must make restitution in the former of a $10,000 cash payment coupled with a collection of hunting rifles, to be delivered by him personally to one of the tribes deep in the country’s interior. At this point, the novel undergoes a dramatic transition, from the nightmarish world of Kafka to the nightmarish world of Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness, a trip – via car, not boat – into the primitive interior of a country that begins more and more to resemble war-torn Iraq or Afghanistan: tribal fighting, militias, landmines, checkposts manned by armed guards. And all the while Tom is making this journey, hoping to pay his debt, his wife and family are growing more and more estranged from him.

Is The Butt allegory or satire? Is it a tragedy or a comedy? Is the bungling protagonist more to be despised, or the native culture that seems to prey on the gullibility of tourists? I did not know at the novel’s opening, had no greater insight at its midpoint, and was perhaps most confused when I turned the final page. What’s worse, I suspect Will Self was every bit as lost as I was while writing it. The Butt has its redeeming aspects – comic moments that stand out, and a prose style that kept me eagerly turning pages, even as the plot seemed designed to stymie my enthusiasm – but not enough to rescue it from a plodding plot.