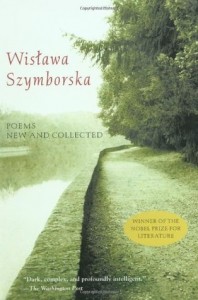

I have to begin by thanking my aunt Sandra, both for recommending Wisława Szymborska to me, and for the gifting of this book.

I have to begin by thanking my aunt Sandra, both for recommending Wisława Szymborska to me, and for the gifting of this book.

Wisława Szymborska (I have given up attempting to pronounce her name) was a Polish poet, born in 1923 and deceased only recently, in February of 2012, and a Nobel laureate. The location and date of her birth, as you might expect, played a significant role in her upbringing, and she spent much of her youth as an advocate for communism, writing poems in praise of Stalin and collective work, but she gradually managed to break free of, and later condemn, her indoctrination, and became a staunch advocate of free speech and individuality. Though my edition samples only those later publications of hers, beginning with Calling Out To Yeti (1957) and ending with The End And The Beginning (1993), there is still an evident progression towards the personal and subjective.

Her poems display a curious mind delighting in the everyday, even the mundane. “Again, and as ever, / as may be seen above, / the most pressing questions / are the naive ones,” she writes in “The Century’s Decline,” and it just these naive questions that preoccupy her poems: what does it mean to be dying, and conscious of the fact, and how do you construct meaning and purpose in face of that impending oblivion? what does it mean to be an individual in a collective, and how do you maintain that individuality, and at what costs? “My choices are rejections, / since there is no other way, / but what I reject is more numerous, / denser, more demanding than before.” Unlike so many of those who seek for the comfort of transcendent meaning, Szymborska is not a mystic. The tedium of poetic astrology is passed over in favor of a natural wonder, one that constantly alludes to the facts of evolution and our cosmological insignificance and yet still manages to celebrate humanity for what we are rather than dwell on what we are not.

Among The Multitudes

I am who I am.

A coincidence no less unthinkable

than any other.

I could have different

ancestors, after all,

I could have fluttered

from another nest

or crawled bescaled

from under another tree.

Nature’s wardrobe

holds a fair supply of costumes:

spider, seagull, field mouse.

Each fits perfectly right off

and is dutifully worn

into shreds.

I didn’t get a choice either,

but I can’t complain.

I could have been someone

much less separate.

Someone from an anthill, shoal, or buzzing swarm,

an inch of landscape tousled by the wind.

Someone much less fortunate,

bred for my fur

or Christmas dinner,

something swimming under a square of glass.

A tree rooted to the ground

as the fire draws near.

A grass blade trampled by a stampede

of incomprehensible events.

A shady type whose darkness

dazzled some.

What if I’d prompted only fear,

loathing,

or pity?

If I’d been born

in the wrong tribe,

with all roads closed before me?

Fate has been kind

to me thus far.

I might never have been given

the memory of happy moments.

My yen for comparison

might have been taken away.

I might have been myself minus amazement,

that is,

someone completely different.

What is this poem if not a celebration of individuality, not myopic or solipsistic or constrained by the ego, but aware of the vastness of possibility (“My choices are rejections…”)? And it is this very awareness (“amazement” born of a mind seeking comparisons) upon which she builds her individuality. Contrast this celebration of self with her fear of what she could have been ,”someone / much less separate,” an ideologue blindly marching in lockstep, content to share a common opinion, or a bee subordinate to the will of the hive, and you begin to appreciate the splendor even of our imperfections because they set us apart.